Evaluating the Social Performance of an Urban Park

By Michael Miller, OLIN Partner & People Lab Leader

Catalyst and Commons

Washington Canal Park was designed to serve rapidly redeveloping Southeast DC, with its mix of office workers, new residents, and long-time, low income residents. An extensive community engagement process informed the RFP and guided the park’s features, including a restaurant, an ice skating rink, interactive fountains, lawns, public art, and environmentally sustainable features such as a water system that treats and reuses park and building stormwater for irrigation and toilet flushing. Canal Park’s clearly articulated social objectives and its participation in the SITES pilot program made it an ideal test bed for post-occupancy evaluation (POE).

Process and Methodology

To focus the evaluation on the goals of the project, the research team drew questions from three sources: SITES documentation, as a normative benchmark; the RFP, as an expression of client and community aspirations; and design team interviews, as an expression of design intent. To address this broad set of questions, the research team employed a mixed-methods approach, including:

Direct observation and time-lapse photography, to capture behavior.

A user intercept survey, to reflect perception.

Key informant interviews with management, maintenance, and retail staff to provide additional perspectives.

Light and sound readings, to supplement use pattern data.

When possible, the team addressed each question with multiple methods to triangulate between observable behavior and stated perceptions.

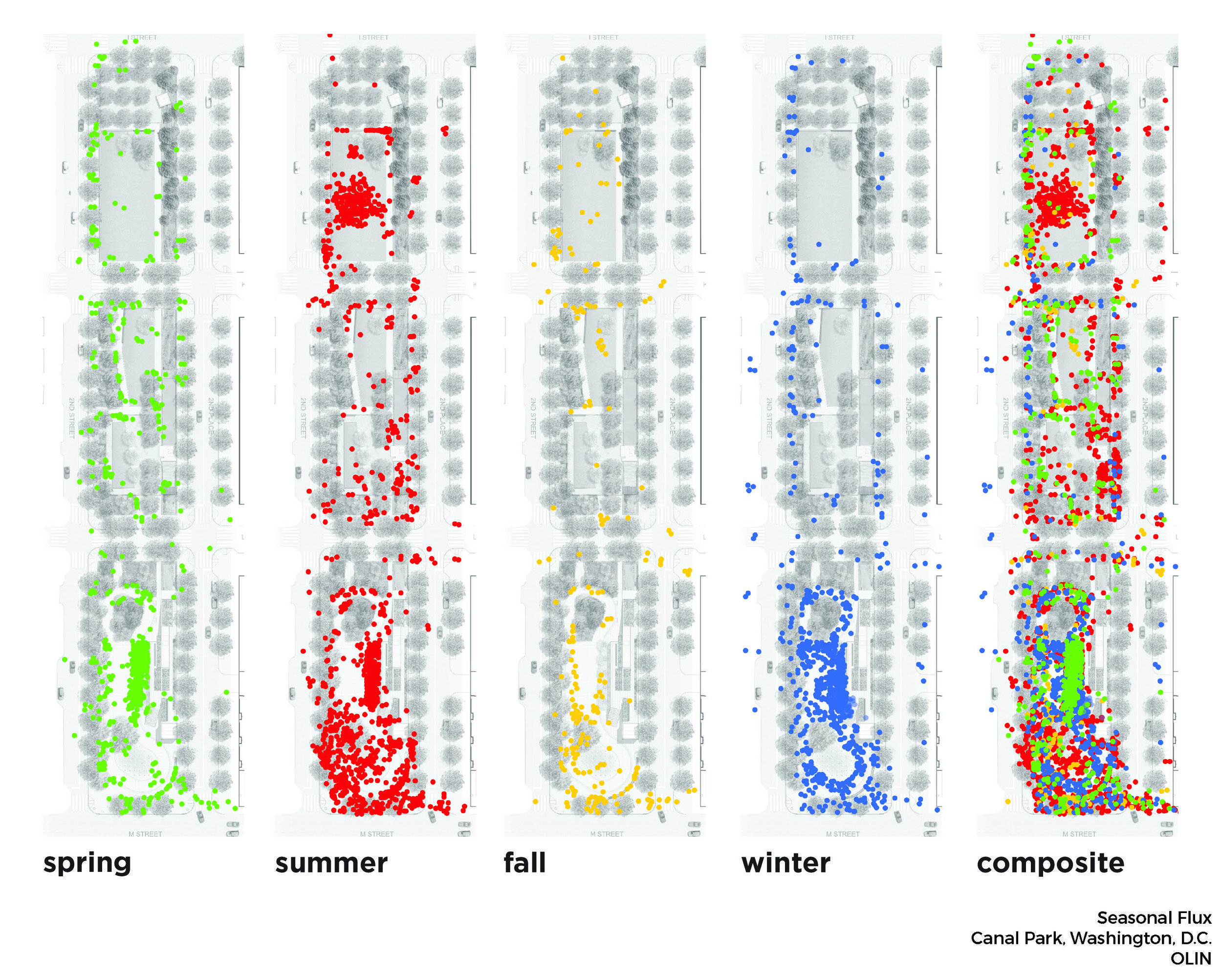

Field research was conducted over the course of a year, with visits in spring, summer, fall, and winter. Data was collected on both weekends and weekdays, from 8:00am until an hour after nightfall. In addition to ordinary days, the research team observed scheduled events and programming, including a movie night and a farmer’s market. At the end of the field research, the team had gathered approximately 100 hours of time lapse footage, 217 questionnaires, 7 key informant interviews, and 20 sample sets of light and sound, gathered from 10 locations in the park. Analysis has yielded at least tentative answers to 99 of the original 105 evaluation questions. In some cases, the findings verify designer hypotheses about how the space would be used, or assertions made in SITES documentation about how given features would perform. These verifications are valuable, in that they provide evidence for our professional intuitions, assumptions, and judgment. In other cases, however, the team’s findings question or complicate these intuitions and assumptions, pointing the way to a more nuanced understanding of user behavior and perception.

Finding #1: Usershed Varies with Program

Canal Park’s use varies from regional to hyper local. Approximately one-fifth of surveyed users come to the park from just three adjacent buildings, reinforcing the critical role that context plays to urban spaces. More than two-thirds of respondents traveled five minutes or less to the park, half of the ten-minute travel time commonly used to determine a service area in parks planning. This was especially true of convenience-driven program: weekday lunches, walking dogs. Yet the park’s destination program, including a restaurant and an ice skating rink, drew users from as far away as a two hour drive. Perhaps the greatest surprise was that the park’s two interactive fountains themselves served as destination draws for families from across DC.

Finding #2: Program for Shoulder Seasons

Unsurprisingly, the park is most popular in summer, when the two fountains are a strong draw and the park’s event calendar is busiest. In winter, the ice skating rink proved a solid programmatic anchor, bringing life to the park when nearby public spaces were empty. Our spring and fall studies, however, revealed gaps in the park’s appeal and programming calendar. On a chilly Saturday in November or April, other nearby parks provided space for active uses like children’s soccer and waterfront running, while Canal Park’s jet fountains played to an empty theater. This suggests that a park with the ambition of year round activity should explicitly target spring and fall programming, rather than relying on typical summer and winter attractions.

Finding #3: Solitary and Social Experiences Can Coexist

SITES Human Health and Well Being credits emphasize the need for both social and solitary experiences within a park. The Canal Park design team had a similar ambition, and posited that the more paved and programmed south block, near busy M Street, would be the most social, while the quieter middle and north blocks would support solitary, contemplative experiences. Our user survey confirmed both social and solitary uses. But the spatial distribution surprised us: there was no discernible pattern. Users sitting next to each other on the same bench at M Street might have widely differing experiences, some experiencing the park as quiet and peaceful, and others as lively and exciting.

Finding #4: If You Want to Build Community, Welcome Dogs and Kids

The client and design team hoped that Canal Park would become a place that forges new social connections. The team found that a quarter of surveyed users made a new acquaintance at the park. When asked how they had met new people, the most common responses involved children, dogs, and park employees. This makes sense: all three create situations that tend to break down boundaries. But given that discussions of fostering social interaction in parks sometimes fix on physical strategies, such as the design and configuration of benches, this finding suggests that certain social configurations, and the programmatic elements that support them, may be more crucial. These configurations might not be universal. In some low-income neighborhoods, dog ownership and dog parks have become symbols of gentrification.

Finding #5: In a Changing Neighborhood, Parks Can Be Common Ground

Given the park’s ambition of serving a diverse, changing neighborhood, the research team wanted to know if users felt welcome in all parts of the park. When asked this question directly, 90 percent of users said yes. The actual demographics of surveyed park users closely fit the neighborhood profile, suggesting that the park is attracting the full spectrum of residents. The team also asked, more subtly, who respondents thought the park was designed for. The most common response (34 percent) was “everybody.” The bulk of the remaining responses were more specific, but still relatively inclusive and reflective of the area’s demographics: the “neighborhood,” “children” and “families,” “office workers,” and “young adults.” This sense of inclusiveness extended to the parks lowest income residents, including ones that had formerly resided in nearby public housing and now lived in the mixed income HOPE VI development that succeeded it. Yet a few of these residents mentioned the price point of the restaurant and ice skating rink, and their inability to afford either. This suggests a cautionary note about for-fee programming in a park intended to act as a common ground in a diverse neighborhood.

Impact

The Canal Park study has been presented at multiple conferences, including the PA/DE ASLA conference, CELA, and the APA national conference, and has been published in the international journal Landscape Architecture Frontiers. OLIN's evaluation also informed a case study of Canal Park conducted by the Landscape Architecture Foundation as part of their Landscape Performance Series.